by Gonzalo Lira

A Termite-Riddled House: Treasury Bonds

When termites eat your house, you don’t notice a thing. You don’t hear a thing, you don’t see a thing—you’re house stands there, silent and staid, while you and your family happily go about your days, without a care in the world—

—until your house crashes on top of your head.

Right now, we are at a stage where Treasury bonds are as weakened as a termite-riddled house. They look fine: Nice glossy coat of paint, pretty shingles, bright clear windows, sturdy-looking plankings on the open-aired porch.

But Treasuries are well on their way to a complete collapse. Why? Because of the way they have been mishandled and mistreated by the Federal Reserve Board, and the U.S. Treasury. Whether by incompetence or by design, U.S. Treasury bonds have become the New & Improved Toxic Asset. The question is no longer if they will collapse—it’s when.

Let me explain why.

First of all, what exactly were Toxic Assets—does anybody remember? I do: They were bonds made out of bundles of dodgy real estate deals. They didn’t seem dodgy at the time. What’s that old expression, “safe as houses”? At the time they were made, those bonds seemed safe as houses. Now we call them “Toxic Assets”—because now, we know better. But back then—before they collapsed—they were called “Mortgage Backed Securites”, or “Commercial Mortgage Backed Securites”, or else “Collateralized Debt Obligations”.

Essentially, all these sophisticated-sounding terms were to emphasize that the bonds were secured loans—the houses and commercial real estate were supposed to back up these debts. If the payments failed, the properties could be confiscated and auctioned off. So the bonds would be repaid. So the bonds were safe—safe as houses. Or so it was thought.

Of course, we saw how that show ended.

For those who missed those exciting episodes, a recap: Sub-prime mortgages began to default first, as the economy slowed down. This in theory should not have affected Mortgage Backed Securities based on those sub-prime loans. But the real estate which had been purchased with sub-primes weren’t worth what they had been purchased for—they were worth much less. So the bonds backed by the sub-prime loans began to explode.

Soon after the sub-primes, alt-A loans and prime loans, and finally commercial real estate—their prices all began to collapse, and so the bonds manufactured out of these loans also began to explode.

All those banks holding all those “safe as houses” MBS’s and CMBS’s and assorted CDO’s all of a sudden found that those bits of paper were not safe as houses. They were so un-safe in fact, that the banks damned near went broke—they would have, too, if it hadn’t been for the Fed and the Treasury, who bailed them out: The Treasury with TARP (cash), the Fed with “liquidity windows” (more cash).

But even that didn’t work—so we got “extend & pretend”, whereby the accounting rules were suspended in order to create the illusion of solvency among the TBTF (Too Big To Fail) banks. (My discussion of that is here.) That’s how bad the Toxic Assets were.

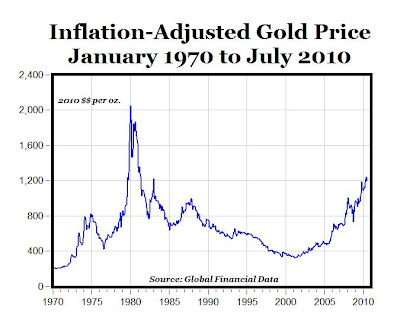

The reason these debts became “toxic” was that it became obvious in 2007–’08 that those bonds would never be repaid. They couldn’t be repaid: The properties which backstopped the value of the bonds had fallen irretrievably in price—or more properly, the real estate bubble which had goosed the valuation of those properties to absurd, Tulipmania levels had finally burst.

So even if the real estate was foreclosed and sold at auction, the holders of these now-Toxic Assets would only receive a fraction of the nominal price of the bonds. What had once been worth 100 was now worth 80, 60, 40, and in some cases, Cop Snacks.

I’ve never liked the term “asset”, when discussing bonds. They’re not “assets”—they’re debt. They’re a loan. And a loan only has value so long as it’s being repaid. If the debtor defaults—or tries to pay back the loan with something of less valuable than what was originally lent out—then this “asset” becomes a loss.

So to prevent these catastrophic losses, Backstop Benny—Ben Bernanke, Chairman of the Federal Reserve—essentially did the ol’ switcheroo on the Toxic Assets: In order to save the banks whose balance sheets depended so heavily on these now-dead turds, the Fed purchased the Toxic Assets at their nominal price. Then the banks—the so-called Too Big To Fail banks—took that cash and purchased U.S. Treasury bonds.

I have yet to find a better chart than this one here, that describes so succinctly how the Fed expanded its balance sheet to bail out the banks. (Hat tip Ashley Huston at WSJ.com: Alex Lowe designed the chart, based on reporting by Phil Izzo—extra-special kudos to them both.)

Meanwhile, the U.S. Treasury, in its attempts to finance bailouts, stimulus, health care, Social Security, and endless pointless wars, went into further debt—to the tune of $1.4 trillion dollars, roughly 10% of U.S. gross domestic product, for both 2009 and 2010.

Or to put it another way—a very scary way—in both 2009 and what’s projected for 2010, the Federal government has issued $1 of Treasury debt for every $1 of tax receipts. Between the actual budget deficit, plus Social Security liabilities, the U.S. Federal government is in the hole for about $13.5 trillion—or roughly 100% of GDP: That is what the Federal government owes. And if 2011 continues to be the same (as is almost certainly to be the case), then another $1.5 trillion or so (give or take a couple of hundred billion dollars) will be added to that tab.

All told, the United States will have a fiscal-debt-to-GDP ratio of 100% this year, and 110% next year—if not higher, depending on the tax receipts in 2011. A lot of wishful thinking is going on for 2012, but the way the numbers are playing out, another trillion dollars’ worth of debt is very likely in the offing—which would put the total fiscal-debt-to-GDP ration to 120%.

(Funny: That number—120%—reminds me of something . . . what was it? Oh! Right! Greece! This past spring, Europe had a medium-sized meltdown when Greece—roughly 2% of the EU as measured by GDP—revealed it was running a 120% fiscal-debt-to-GDP ratio. The Europeans and the IMF finally caved and bailed out Greece. Ah, the Greeks! But I digress, sorry—after all, the United States is not Greece. The United States has absolutely nothing in common with Greece—not at all! First of all, buddy, and for your freakin’ information, the United States is roughly 45 times the size of Greece, and . . . oh . . . wait a sec . . . )

Let 2012 take care of 2012—right now, September 2010, we have 100% fiscal-debt-to-GDP, in an environment of falling tax receipts and more strains on the various social safety nets. Right now, we have debt matching tax receipts dollar-for dollar. Right now, the interest on the outstanding debt, for 2010 according to government projections, is $375 billion—in other words, 25¢ of every dollar of tax receipts goes to pay interest. Right now, with recent economic numbers, the likelihood of a turn-around are unlikely—so because of the inevitable political pressure come the winter, more “stimulus” is likely in the offing.

Meaning more Treasury bonds, floating out into the market.

But who is buying all this new Federal government debt? Why, that’s very simple: The Federal Reserve.

The reason that the Federal government could go into the aforementioned massive spending spree was precisely because of the Federal Reserve’s bail-out: The Fed created money out of thin air (as is their power), in order to buy Toxic Assets from the Too Big To Fail banks. The banks, in turn, took this cash and bought Treasuries—which financed the Federal government’s deficit.

This is what I call Stealth Monetization: Unlike in some banana republics, which dispense with the niceties and simply turn on the printing presses whenever they need more money to spend, the U.S. Federal government and the U.S. Federal Reserve got creative, and used the TBTF banks to essentially hide the monetization of the fiscal debt in plain sight.

Many people complain that the bail-out money the TBTF banks received was never lent out—oh, but they’re wrong: The money was lent out. It was lent out to the Federal government.

After all, what did the TBTF banks do, with all that cash they got from the Federal Reserve for unloading all those Toxic Assets? Why, they went and bought themselves boatloads of Treasury bonds.

It’s been the Federal government that has been “mopping up excess liquidity”—mopping it up and spending it on stimulus that doesn’t work, wars that can’t be won, dodgy dinosaur-projects that aren’t going to do squat to improve people’s health. That’s why the TBTF haven’t been lending money to businesses and “getting the economy back on track”—they’ve been too busy lending to the Federal government.

Clever people call Treasuries “assets”—but like I’ve said, I’m just stupid: I just call it debt. When I look at all this Federal government debt—unprecedented amounts of fiscal debt—I can’t help but notice that it is all unsecured—because it is unsecured. At least Toxic Assets had something backing them up, even if they were worth much less than advertised. Treasury bonds, on the other hand, are based only—solely—on the “full faith and credit” of the United States Federal government.

Y’Know: The one in Washington. The same U.S. Federal government that is running 100% debt-to-GDP ratios this year, 110% next year, and likely 120% the year after that—if not more.

Mm-hmm . . .

What happens when a debtor becomes so over-extended that he cannot possibly pay back his loans? Naturally: They default—or they try to wriggle their way out of the debt, by giving you something less valuable than what you are owed.

It is not controversial to say—and indeed, it is widely discussed—that the U.S. Treasury has only two options: Default on Treasury bonds, or debase the currency by way of inflation, so that the nominal value of Treasuries is stable, but their real value decays by inflationary attrition.

Default is politically unacceptable—apart from pissing off foreign Treasury holders, it would cause havoc in America if the Federal government woke up one day, clapped its hands like a schoolmarm, and announced to the world, “Okay Treasury holders! Time for a haircut!” Default ain’t gonna happen.

So that leaves “controlled” or “induced” inflation—the only method for the Federal government to get out from underneath this debt.

Backstop Benny is doing his damnedest to bring about precisely this scenario: He is trying to print the economy out of this Global Depression. With QE, the recently anounced QE-lite, and the likely-to-be-coming-soon QE2, Bernanke is going to pump more and more money into the system—“Print ’til you puke!!” seems to be his motto.

Bernanke is being egged on by everyone, from Paul Krugman to the Republicans to Larry Summers and Tim Geitner—everybody wants him to print more: Either because they want more fiscal spending (Krugman, et al.), or because they want asset prices to be pumped up again to unnatural highs (Wall Street and their Washington lackeys).

And Benny is obliging. The way Bernanke is doing this printing is by buying Treasuries. The Federal Reserve buys Treasuries and squirts some more dollars into the system—just as he propped up the prices of Toxic Assets by buying them up, when there was the need.

Yields of Treasuries are at absurd lows, there is a veritable T-bond rally every single day that equities drop even just a bit—in other words, Treasuries are in a bubble. Why? Because the market knows that Bernanke and the Fed will backstop Treasuries—

—backstop them right off the cliff.

The more the Fed prints, the more it encourages the Federal government to “stimulate”—id est, go further into debt in an attempt to grow the economy out of this Depression by way of fiscal spending. But as I said, right now, 25¢ of every dollar of tax receipts goes to pay interest on the fiscal debt. How long before 50¢ of every dollar goes to pay interest? 100¢ of every dollar? Is that when the fiscal debt finally becomes insurmountable?

Or will there be a Moment of Clarity in the markets? Will there come a day when the bond markets collectively realize that Treasuries will never ever be repaid—cannot be repaid? And when that day comes, when that Moment of Clarity falls on the markets, will it spark a panic?

In two previous posts, I essentially said “yes”: “Yes” to a collective Moment of Clarity, “yes” to a panic in Treasuries. I further argued that such a panic would lead—inexorably—to a flight to safety in actual, physical commodities, which would then result in a massive hyperinflation that would kill the dollar dead. Part I is here, Part II is here.

What is most important is, I do not know when such a Moment of Clarity will occur—but I have no doubt that it will occur. Inevitably, unavoidably: Treasury bonds are bound to collapse, triggering the sequence of events that I have described.

Plenty of people disagree with me. Actually, most people disagree with me.

Weirdly, plenty of people told me in no uncertain terms that, not only would there never be a panic in Treasuries—these people claimed that there couldn’t be such a panic. A couple of these people claimed (I swear to God) that it was systemically impossible for there to be a panic in Treasuries—“Because the government can just print its way out of a panic!”

Uh-huh. So no hyperinflation after a Treasury bond collapse, ’cause the government can—y’know—print all the money needed to shore up Treasuries and avoid hyperinflation. Okay.

The people who defended this insane argument are under the spell of MMT—Modern Monetary Theory. It’s currently the most fashionable dismissal of the importance of Treasury over-extension. People in this camp effectively say, “Treasury debt doesn’t matter!”, and explain how government debt is basically a numbers game.

According to this theory—which is just a modern-day retelling of the chartalist myth—all money is basically government chits, which are moved around within a game-board, said game-board being owned and controlled by the government. According to MMT, governments which issue their own currency may go into as much debt as they wish, certain and confident that nothing bad will happen because the government controls the currency. In other words, macroeconomically speaking, MMT claims that it’s a government’s world—we only live in it.

My objection to this, in snooty eccy terminology: I think that these MMT macro-economic theorists are purveyors of an interesting new meta-neo-Keynesianist world-view. It seems they are employing a closed-system, zero-sum proto-monetarist model. This model—though compelling—does present certain structural issues and disappointing limitations, vis-á-vis the uses of a reserve currency, which might make the theory less than apropos, were it to face a real-world scenario. Or not.

My objection to this, in just plain ol’ regular words? I think this MMT theory is full of shit, propagated by fucking idiots.

MMT is just a clever way to justify insurmountable levels of fiscal debt—it’s a rationalization of this insurmountable debt, using a veneer of economic terminology to cloak the purveyors’ political ideology of spend!-spend!-spend!-your way out of a recession or depression: In other words, Keynesianism-redux. Keynesianism on steroids—Keynesianism gone fucking in-sane.

(I’m going to write a detailed take-down of these MMT fools in a couple of weeks. But for now, let me limit myself to just a couple of paragraphs.)

These irresponsible peddlers of MMT claptrap—because that’s what they are, irresponsible buffoons for peddling such irresponsible, arrogant bullshit—simply do not understand what money is: It is a medium of exchange. The government—which controls this medium of exchange, especially in a fiat currency—is supposed to be the honest broker between economic participants who use this medium of exchange for their transactions.

A government issues the medium (the currency), and the government can debase it at will, for whatever reasons it deems worthy. But if the medium—the currency—is debased to a tipping point, then the economic participants will no longer believe in the currency’s worth. They will therefore run from the currency, and turn elsewhere to fulfill the need that money satisfies, which is: To store wealth, and to act as a medium of exchange.

If the dollar and Treasury bonds are pushed hard enough—that is, debased hard enough—there will come a point where people will lose trust in them both, and not want them. It’s one thing if a currency organically inflates by way of ordinary demand on consumables and expansion of credit—that’s just normal fiat currency wear-and-tear. It’s quite another if economic parties realize that a government is deliberately trying to debase the currency, in order to get out from under insurmountable debt.

If people no longer trust dollars as a medium of exchange and Treasuries as stores of value, where will they go? They will leave both and go to something else—commodities, as I have argued. And when that day comes, people will do anything to get out of the dollar and Treasuries, and into something that is stable in terms of value storage and medium of exchange.

MMT doesn’t see this—it just sees spread-sheets and board-games. This story here, which giddily, girlishly describes Federal Reserve drones “printing money”—and how wonderful and magical that process is—is pretty indicative of the fundamental detachment from reality of this world-view.

It’s why MMT fails at describing both reality, and predicting the future. It’s why—among other reasons, which I will discuss more fully in another post—MMT is a big ol’ steaming crock of shit.

MMT is one theory as to why nothing bad will happen to Treasuries.

The other theory—much more sensible, and backed up with empirical evidence—is what I’d call the Japan Is Us theory of Treasury bond stability. It’s the only truly serious challenge to the argument of Treasury bond collapse which I am arguing. Therefore, it’s a challenge that must be met.

On the blogosphere, Michael “Mish” Shedlock is probably the smartest proponent of the Japan Is Us theory.

I have a lot of respect for Mish—he was one of the very few serious commentators who argued that the U.S. economy was going to experience deflation. He argued that position literally years before it caught on. People now—in 3Q of 2010—are wising up to deflation. Because of Mish’s insights, I was on to deflation as of 3Q of 2008—and was fortunately able to plan accordingly.

Mish also thinks I’m full of it, for claiming that there’ll be a Treasury bond collapse, commodity spike and then hyperinflation.

His rationale is, we are experiencing deflation (which I agree). This deflation has been brought about by destruction of credit (check again), brought by the bursting of the housing bubble and the concomitant reduction in mortgages and loans (check once again).

Mish further argues that, like Japan, the U.S. Federal government will spend-spend-spend on all sort of needless projects, but that the deflation is much stronger. Therefore, no matter how much the U.S. spends, there is no way to escape from a Japan-style Lost Decade (or two) of stagnant growth and systemic deflation.

This is where we part company.

Mish is convinced that through these deflationary years/decades, Treasuries will continue to be the only safe store of value. From a recent post, here’s a representative quote:

I do think corporate bonds, especially most junk is playing for the greater fool. regards to treasuries, there is going to be an exit problem for sure, but that could be years away. In Japan, yields stayed low for a decade. Why can’t it happen here?

Yields certainly might stay low for an extended period. Whether or not they do remains to be seen.

(The underlining is mine.)

Mish thinks that there’ll never be a Moment of Clarity, regarding Treasuries. He admits that there might be an “exit problem” in Treasuries, but vaguely posits that that might be “years away”. In the meantime, he thinks that Treasury yields will remain low, prices high (or go even higher), as companies and banks basically “keep money under the mattresses”.

Mish has a good case in arguing for the Japan Is Us theory—but he is wrong, on two fronts.

First, Mish doesn’t realize that Federal Governments’s deficit spending is rapidly approaching its limit. Because unlike Japan in 1990, when its deflationary death-spiral began, the U.S. Federal government started this depression already with a massive deficit. The eight years of Bush 43, to be precise, were all borrow-and-spend years: In those eight years, the fiscal deficit had already goosed the economy.

That’s why the massive stimuls Obama implemented hasn’t really helped—the economy is already hung-over from the Bush stimulus years.

Besides—and so obvious that it shouldn’t even be up for debate—yearly fiscal deficits of 10% of GDP per year are simply unsustainable. I don’t care what argument you make, deficits of this ever-increasing size will lead to a collapse in the economy. Certainly a blow-up in Treasuries—the instrument of this deficit—long before.

Mish further fails to realize that the Federal Reserve has abandoned both of its mandates—to fight inflation and to maintain full employment—in favor of its new mantra: Maintaining aggregate asset price levels. Whatever it takes. This means essentially inflating asset price levels back to pre-Depression levels.

Everything the Fed has been doing since September 2008 has been in the service of this goal. The MBS buys, the alphabet-soup of liquidity windows, QE, now QE-lite, QE2 soon to come—the Fed is hell-bent on maintaining the bubble it created between 1987 and 2007.

Since September 2008, the way the Fed achieved this goal was by effectively nationalizing private debt, and turning it into public debt—one look at the Fed balance sheet is enough to convince any skeptic. This means that all the bad debt accumulated during the last two-and-a-half decades have been effectively turned into Treasuries.

So Treasuries are getting squeezed and pulled two ways: By the U.S. Federal government, and by the U.S. Federal Reserve. Because of the massive fiscal debt of the Federal government, Treasury bonds will not be repaid, at least not in real terms. And because of the Federal Reserve’s constant goosing of their prices in order to both maintain low interest rates and prop up asset prices, Treasury bond prices have left planet earth altogether, and are in the realm of Bubble-land.

In a couple of private e-mails, Mish objected to—and dismissed—my Treasury-run/commodity-moonshot/hyperinflation scenario altogether. According to him, I was arguing for a Shazaam! moment: When all of a sudden—for no reason whatsoever—people would collectively panic and—Shazaam!—they would exit Treasuries en masse.

Mish is actually right—that’s what I’m saying. I pompously call it a “Moment of Clarity”, Mish more cuttingly calls it a Shazaam! moment.

But that is, in essence, what I am arguing: Because in a termite-riddled house, no one can predict when the house will collapse—but we all know deep in our bones that it will collapse. So the second you hear a creak in the plankings, what do you do? You run for the exits.

I have no idea when that Shazaam moment will happen: Tomorrow, next month, next year. But it will occur—because everybody knows that Treasury debt cannot be repaid. So it’s not a question of if—the damage has been done, and is irreparable. It’s now just a question of when.

I hope I have explained why.

![[ROI_100524]](http://sg.wsj.net/public/resources/images/OB-IP413_ROI_10_NS_20100524192106.gif)